h/t Peter @ Bayou Renaissance Man

Vegas shooting ER team

Ironman, Captain America, Superman, and Batman

I’m a night shift doc. My work week is Friday to Monday, 8 p.m. to 6 a.m. Most people don’t want to work those shifts. But that’s when most of the action comes in, so that’s when I work. It was a Sunday night when the EMS telemetry call came in to alert Sunrise Hospital of a mass casualty incident. All hospitals in Las Vegas are notified in a MCI to prepare for incoming patients.

As I listened to the tele, there happened to be a police officer who was there for an unrelated incident. I saw him looking at his radio. I asked him, “Hey. Is this real?” and he said, “Yeah, man.” I ran down to my car and grabbed my police radio. The first thing that I heard when I turned it on to the area command was officers yelling, “Automatic fire…country music concert.” Ten o’clock at night at an open air concert, automatic fire into 10-20 thousand people or more in an open field—that’s a lot of people who could get hurt.

At that point, I put into action a plan that I had thought of beforehand. It might sound odd, but I had thought about these problems well ahead of time because of the way I always approached resuscitations:

Preplan ahead

- Ask hard questions

- Figure out solutions

- Mentally rehearse plans so that when the problem arrives, you don’t have to jump over a mental hurdle since the solution is already worked out

It’s an open secret that Las Vegas is a big target because of its large crowds. For years I had been planning how I would handle a MCI, but I rarely shared it because people might think I was crazy.

It's written by the senior ER doc on duty, and so from his perspective. Taking not one thing from him, but the reality is, while his plan helped, it was a team effort.

For instance, they had 6 ER docs working that night, including a Trauma surgeon and Trauma resident.

We also initiated our hospital’s “code triage,” in which staff from upstairs would come down to help by bringing down gurneys and spare manpower. We took all of our empty ED beds and wheelchairs out into the ambulance bay. Anybody who could push a patient, from environmental services to EKG techs to CNAs, came out to the ambulance bay. I said to the staff, “I’ll call it out. I’ll tell you guys where to go, and you guys bring these people in.”

Unstated were how many RNs on hand, but in a 36-bed main ER, they had 10+, which swelled to probably 20-50.

What were they doing?

At that point, one of the nurses came running out into the ambulance bay and just yelled, “Menes! You need to get inside! They’re getting behind!” I turned to Deb Bowerman, the RN who had been with me triaging and said, “You saw what I’ve been doing. Put these people in the right places.” She said, “I got it.”

And so I turned triage over to a nurse. The textbook says that triage should be run by the most experienced doctor, but at that point what else could we do?

Better late than never, doc. Nurses run Triage 24/7/365 everywhere. Should've seen that coming and made the call a lot faster.

We were in the hallway of Station 1 with the beds side by side. We were butt to butt intubating these three people. “I need etomidate! I need sux!”

Up until then, the nurses would go over to the Pyxis, put their finger on the scanner, and we would wait. Right then, I realized a flow issue. I needed these medications now. I turned to our ED pharmacist and asked for every vial of etomidate and succinylcholine in the hospital. I told one of the trauma nurses that we need every unit of O negative up here now. The blood bank gave us every unit they had. In order to increase the flow through the resuscitation process, nurses had Etomidate, Succinylcholine, and units of O-negative blood in their pockets or nearby.

Another good call. But "Duh".

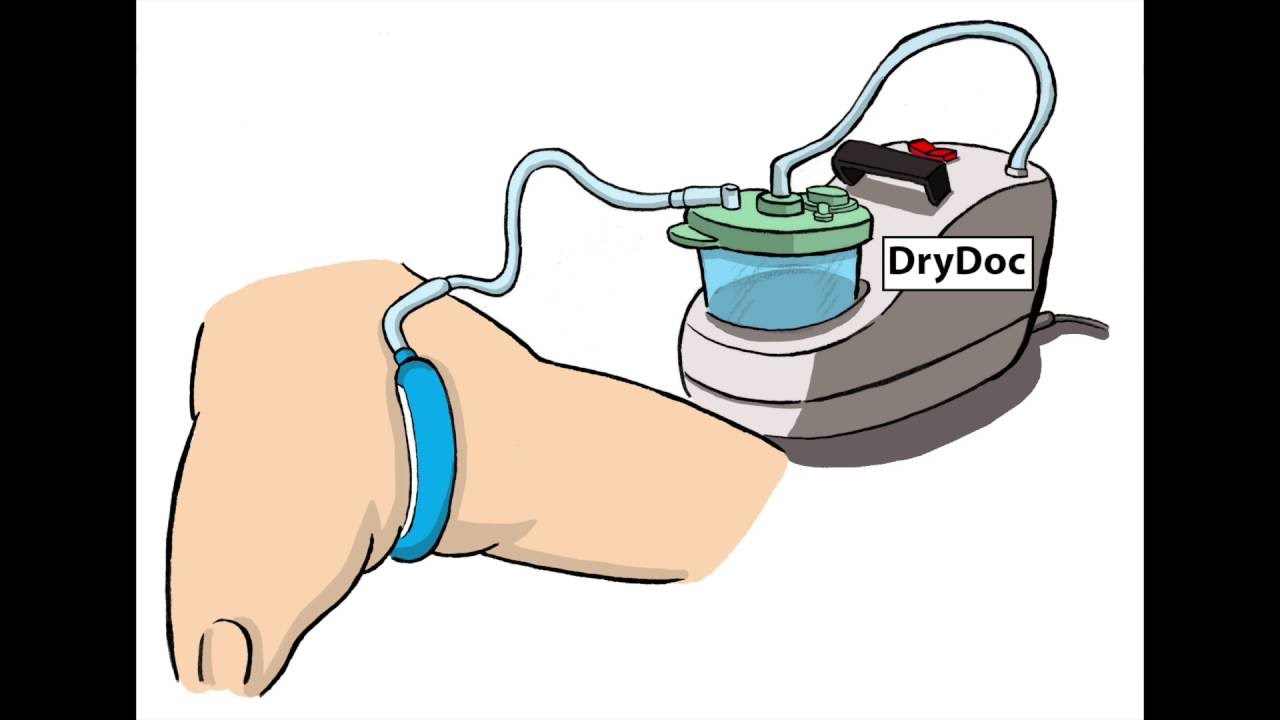

By this time, all the patients had bilateral IVs. As the orange tags and yellow tags would become red tags, it became very apparent that those early IVs, put in while patients still had decent veins, were lifesaving. As the patients decompensated, we had adequate access to rapidly transfuse and stabilize patients. If we didn’t have that early IV access, we would have spent valuable time trying to cannulate flat veins.

Putting in IVs: nursing skill. Twenty-forty/night. That's why all those patients magically had bilateral IVs.

Cannulating flat veins: what ER docs do when patients don't have anything better.

So again, "Duh."

Throughout the night, I would look up from what I was doing and scan the room to see if anyone was crumping. I noticed a choke point forming for CT. We were now left with stable yellow tags. These patients needed CAT Scans. Typically, the CT Tech picks up the patient, transfers them onto the scanner, and then they bring the patient back. These yellow tag patients were shot in the torso, but for some reason were stable even after 2 or 3 hours. I told the CT Tech, go over to the CAT scan machine, and sit behind the controls. “I don’t want you to move. You’re just going to press buttons for the rest of the night.” Then I took every nurse that was free—at that point we had a lot of extra staff—and told them that all the people who needed CAT scans needed to be lined up in the ambulance hallway outside of CAT scan. We placed monitors on them, and nurses watched them. Then the nurses assisted getting each patient on and off the CT, and then back over to Stations 2 and 4. I called it the CT Conga Line.

And yet again: Good improvisation, excellent use of resources, poor foresight.

But how many hospitals deal with 250 GSWs in 6 hours? So far, just this one.

I identified another choke point with the green tag patients. Many were shot in the extremities. They had potential fractures or open fractures and needed X-rays. The standard way of doing things is taking the patient for an X-Ray, then sending it off to the radiologist so they can read it in their reading room. That was just going to take too long. So I told our CEO, Todd Sklamberg, “I need a radiologist here in the ER. I’m going to attach him to an X-Ray tech because our machines have little screens on them.” They X-Rayed patients, the radiologist read off the screen, and we would decide on disposition right there.

Another genius move. Put the people where the work is, and roll the patients past them.

Create flow; eliminate the bottlenecks, choke points, and single-points-of-failure.

IOW, destroy almost everything we do now, to do what you have to do then.

In the end, we officially had 215 penetrating gunshot wounds, but the actual number is much higher. As I would circle the ER “looking for blood,” I would hear the green tags say, “You know what? I’m not that bad—I’ll be fine.” Over time, they would walk out without getting registered. Our true number was well over 250.

The surgery team performed an unprecedented feat that night. The numbers speak for themselves. In six hours, they did 28 damage control surgeries and 67 surgeries in the first 24 hours. We had dispositioned almost all 215 patients by about 5 o’clock in the morning, just a little more than seven hours after the ordeal began. That’s about 30 GSWs per hour. I couldn’t believe that we saved that many people in that short amount of time. It’s a testament to how amazingly well the hospital team worked together that night. We did everything we could.

Improvisation: 10

Pre-planning: 5

Success: 9.9

Takeaway: Plans fail. So does planning. People - who can improvise on the spot - save your ass. And in this case, 200+ patients too.

Top to bottom, these folks were rockstars, when it counted.

Hopefully some of the two dozen nurses and hordes of other staff members will be telling their stories from that night, especially for lessons learned from all the other perspectives.

Superpowers, bitchez.

F**k a cape and tights; superheroes wear scrubs and stethoscopes.

And they kick Death's ass.

.jpg/1200px-Toiletpapier_(Gobran111).jpg)